What do you see when you look at this oil drain plug? Do you see the work of a mechanic who could not be bothered to wipe off the area around the drain plug both before he removed and after he screwed it back in after an oil change? On the other hand, do you see an oil drain plug that has started to leak because a mechanic had failed to tighten it properly after an oil change?

Either interpretation could be correct, but this story, in which this writer appears as a consultant, revolves around the second interpretation, and it recounts how a mechanics’ failure to tighten an oil drain plug caused not only major inconvenience to the customer, but also huge financial losses for his employer, and a third party engine rebuilder, albeit by proxy. Let us start this cautionary tale by stating-

The details of the problem (as they were related to this writer) were simple; the customer had noticed a small patch of oil on his garage floor and took his vehicle, a Kia SUV with a 2.4L engine, to his usual service provider to have the oil leak found and repaired. Upon investigation, it turned out that the copper sealing washer under the sump drain plug appeared to be damaged through over-use, and needed to be replaced.

The customer accepted this diagnosis and asked that the oil and oil filter also be replaced during the sealing washer replacement. Thus, the washer was duly replaced, the filter was changed, the engine was filled with synthetic oil, and the oil service indicator was reset. The customer collected his vehicle later that day but returned it less than an hour later- on the back of a recovery truck.

We won’t repeat the subsequent conversation between the highly upset customer and the owner of the small workshop here, for obvious reasons. What we can say is that the customer used very colourful language to describe the cloud of white smoke that suddenly appeared from under the vehicle, the smell of burning oil, and his emotions when both the oil pressure and MIL warning lights illuminated while he was driving home on the freeway. According to the workshop owner, the customer also banged his fist on the office countertop to imitate the series of thudding/knocking sounds he heard coming from the engine just before it died.

There is much more to relate, but in the interests of brevity, we will only say that the customer was provided with a rental vehicle similar to his own for the duration of what was to follow, which brings us to possible -

According to the workshop owner, the Kia's engine could not be cranked with the starter motor, because it seemed, as he put it at the time, as if the engine had been fused into one solid block of metal. Therefore, the next thing they did was to put the vehicle on a hoist to remove the sump to check for possible damage to the crankshaft, which was when he noticed that the oil drain plug was missing from the sump.

Now we know that oil drain plugs don’t just fall out of sumps. The only way an oil drain plug can fall out is if had not been tightened correctly, but the responsible mechanic steadfastly maintained that he was "fairly sure that he had tightened the plug correctly”, and that “he had even torqued it to specification to prevent just this thing from happening”.

There was some back and forth on his version of events, but since the plug was missing, the consensus in the workshop was that the drain plug had not been tightened, and that was all there was to it. Since the workshop owner understandably no longer trusted the hapless mechanic as he used to, he instructed a different technician to remove the sump so he could assess the-

Removing the sump was not easy, but contrary to his expectations, the workshop owner found that while two main bearings had transferred some metal on to the crankshaft, this could be repaired by grinding the crankshaft to the next undersize. However, removing the big end bearing caps showed that the big end journals were damaged beyond repair but his choices at this point were limited since he did not carry insurance against faulty workmanship.

Therefore, the workshop owner instructed some mechanics to remove the engine and to remove the pistons to see if the cylinder bores could be saved. Fortunately, for him, the damage was limited to the bottom end, meaning that either he could have the engine rebuilt, or he could replace it with a used engine- depending on which option was the most cost-effective.

It turned out that rebuilding the engine would be cheaper by a significant margin, so the engine was shipped off to a local machine shop, with instructions to re-bore the cylinders and to assemble the engine with new pistons, rings, big-end bearings, a new oil pump, and a properly refurbished crankshaft. In short, the engine should be ready for installation into the vehicle when it was delivered.

The machine shop delivered the rebuilt engine about ten days later (along with their hefty bill) and it was duly installed into the KIA, which was when more trouble started and where this writer properly entered the story. Here’s what happened-

According to the mechanic that installed and commissioned the engine, it cranked a bit longer than it should have on first start-up, but it did start and ran smoothly for a few seconds before the MIL lamp illuminated. The mechanic turned the engine off to see if “something would reset itself”, and although it again cranked for longer than usual, it started again, and again ran smoothly for a few seconds before the MIL lamp came on again. The mechanic added that at no point were any mechanical noises and/or noticeable misfires present, and all other warning lights remained off.

Thus, to see if he could determine the problem, he connected a scan tool and found only one active code, this code being P0336 – “Crank Position Sensor Circuit Range Performance". Assuming that one or more connectors might not be properly seated, the mechanic checked the relevant wiring and connectors but found no obvious faults or defects.

All connector pins and wiring were undamaged and all locking tabs were properly secured, so his next step was to order a new crank position sensor from the dealer on the assumption that the original sensor might have been damaged during the engine removal/installation. Replacing the sensor did not resolve the problem, and since the workshop did not own an oscilloscope, the mechanic recommended to his employer that this writer be called in to consult on the problem because he (this writer) had solved several problems for them before, which raised some-

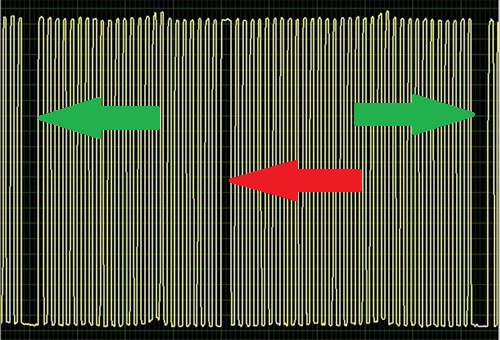

This writer could find no obvious issues during a visual inspection of the engine but his KIA-specific scan tool confirmed the existence of code P0336, which seemed strange because the engine ran without obvious or detectable misfires. The next obvious step was to scope the crank position sensor’s output signal, which produced this rather peculiar waveform-

Image source: https://www.searchautoparts.com/sites/www.searchautoparts.com/files/images/Fig6_5.jpg

This expanded waveform shows the output signals from the crank position sensor over one engine revolution. The two green arrows point to the gaps created by the reference point on the reluctor wheel, while the red arrow points to a curious gap in the sensor’s output. Service information stated that the reluctor wheel on this engine has 58 teeth, but despite several recounts of the wave peaks, this writer could only count 57 peaks- equating to 57 teeth on the reluctor wheel. However, on this engine, the reluctor wheel is integral to the crankshaft, which means that there are no easy ways to verify the condition of the teeth on the reluctor wheel. Nonetheless this writer has often found new electronic parts to be defective, so based on the assumption that there might conceivably be some sort of issue with the new sensor, the new sensor was replaced with the original crank sensor.

The original crank position sensor, however, produced the same waveform as the new sensor, which meant that the problem was directly related to the reluctor ring on the new crankshaft, as unlikely as that seemed to be at the time. Yet, stranger things have happened- as we all know.

There was a bigger problem though, and that involved difficult questions like whose fault it was, and who was ultimately going to pay all and any additional costs. At this point though, there was nothing more this writer could contribute towards resolving the issue until the new crankshaft had been inspected to verify to the condition of the reluctor wheel, which meant at least removing the sump again.

Of course, this meant more lost time and labour, so the obvious solution was to return the vehicle with the engine still installed to the machine shop for them to find the problem since they assembled the engine. The machine shop's management was not at all happy with this turn of events because it was going to cost them money, but here is-

Image source: https://www.searchautoparts.com/sites/www.searchautoparts.com/files/images/Fig8_3.jpg

This image shows the actual crankshaft and reluctor wheel from the problem KIA but note the red arrow that indicates a broken and damaged tooth on the reluctor wheel. From this image, it is clear that the crank position sensor could not create a signal as the broken tooth passed in front of the sensor, which explains the curious drop out in the sensor’s output waveform, and it begs the question of how it is possible to assemble an engine without noticing a damaged reluctor wheel on the crankshaft.

This writer was not present when this issue was discussed by the principal actors in this comedy of errors, but the gist of it was recounted to him by the mechanic that installed the rebuilt engine. This is what happened, according to this seemingly reliable source-

The person operating the crank grinder at the machine shop was instructed to remove the reluctor wheel from the damaged crankshaft and to fit it to the used crankshaft that was to be installed into the KIA engine, but only after he had ground and checked the crankshaft. However, the machine operator chose to ignore these instructions and fitted the reluctor wheel to the crankshaft before placing it in the machine.

It was never explained why he did this, but he did admit that he “may have” bumped the reluctor wheel against a part of the crank grinder when he removed it from the machine, which was when the tooth “might have” broken off the reluctor wheel. This genius did not think that the broken tooth would have much of an effect on the engine so he kept quiet and blithely passed the crankshaft along to the engine assembler, who somewhat strangely, failed to notice the missing tooth on the reluctor wheel during the process of assembling the engine, which begs this question-

It is tempting to say that all the blame for this sorry tale attaches to the mechanic who had failed to tighten the oil drain plug, but if one were to be pedantic, one could say that there is plenty of blame to go around. However, this writer knows the workshop involved rather well, and he has witnessed mechanics being pulled of jobs to “have a quick look” at issues on the vehicles of walk-in customers on several occasions. We all deal with multiple distractions every day, and who among us can say that we have never forgotten to tighten or check something or other when we are trying to get some work done between distractions?

It is also tempting to say that some blame attaches to the owner of the workshop because of his bad habit of pulling mechanics off jobs to attend to walk-in customers. However, those among us with management experience know how difficult it can sometimes be to attract new business while having to deal with operational issues that can sometimes suck objectivity and sound judgment out of you.

This writer cannot express an opinion on the events that took place at the machine shop because he does not know anything about how things are done there. Nonetheless, unlike the original workshop where the problem started, and where only one person was involved, the broken tooth on the reluctor wheel went unreported by one person and unnoticed by a second, which seems to point to simple negligence on the part of both persons. However, this writer cannot say how many distractions each of these persons have to deal with during their days at work, which brings us to-

While replacing the crankshaft a second time resolved the issue, the customer was less than thrilled about the affair, and he has never been back to the workshop he had supported for many years. The loss of a regular customer is something no small workshop can afford but there were other, equally serious effects, such as the fact that everybody involved in this incident lost money, and a lot of it, too.

In absolute terms, the workshop owner spent roughly 100 times the amount of money on rebuilding the engine than he would have earned from the simple oil drain plug repair. Worse, though, this estimation excludes potential profits from the time that could have been billed on other jobs by the mechanic who removed and reinstalled the engine, as well as the costs of providing the customer with a rental vehicle for two weeks.

Taken together, these losses represent money that can never be recovered, and while it might be easy to say that proper, comprehensive insurance is the answer to prevent or mitigate these kinds of losses, one could reasonably also ask if small workshops really need insurance against mechanics failing to tighten oil drain plugs.

Based on this sorry saga, it seems that sometimes, they do.