Few of us have ever had the opportunity to diagnose and resolve major issues on exotic supercars. Many of us, on the other hand, would no doubt jump at the chance to do just that, but the cautionary tale that follows should (if nothing else) motivate most of us to rethink our ambitions to work on supercars more often than once or maybe, twice in our lifetimes.

This tale involves a second-generation, 2013 Lamborghini Gallardo, or to give it its full name, a Lamborghini Gallardo LP570-4 Superleggera with major valve timing issues that took us three weeks to diagnose, but then declined to repair. This is a fairly involved tale, so let us start by providing-

Before we state the actual situation, we must explain that when this writer retired from active participation in the car repair industry a few years ago, he sold his successful workshop as a going concern to his chief mechanic, who later sold half of the business to the resident diagnostician, whom we have often featured here.

This writer then embarked on a kind of second career as a mobile diagnostic consultant soon after and sometimes even at his former business establishment, but only rarely, since the combination of the diagnostician and the chief mechanic were a formidable team that thrived on challenging situations. Thus, when they invited this writer to consult on the problem with the Lamborghini, he accepted because he was more intrigued by the challenge than he was confident of being able to resolve it.

Besides, the car’s owner turned out to be a long-time regular customer who had paid this writer’s former business several small fortunes over many years for servicing and maintaining his fleet of 80 or so delivery vehicles. Therefore, this writer agreed to “come over and have a look” at the problem Lamborghini. The diagnostician ended the call by saying that despite their best efforts to prevent the customer from leaving the car with them for the night, they could not persuade the car’s owner to take it to a dealership instead, because we had no experience of exotics in general, and of Lamborghinis, in particular.

The customer merely stated that we had never done him wrong before and that he was fully confident that we would not do him wrong now. However, this statement must be judged against the fact that while we knew the customer owned a small collection of vintage exotic cars, we had never even serviced any of them, much less resolved major mechanical issues, which brings us to-

We referred to the Lamborghini as “loathsome” in the title of this piece, but that was not something we came up with; this was how the car’s owner referred to it when he met this writer at the workshop the next morning.

It turned out that he was more than a little disillusioned with what he thought was a bargain when he saw it advertised as part of a deceased estate that was being sold off. According to the auctioneer, the car had not run for several years, but that it was in a specialized storage facility that kept it in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment. Apparently, this hugely expensive service included, among other things, lifting the car off the ground to prevent flat spots from developing on the tyres, keeping batteries fully charged and maintained, and starting it regularly to keep the engine lubricated.

We had only heard of these kinds of services that are available to the super-rich, but we took the customer’s word for it. In any event, he bought the car unseen and untested three weeks ago for about 70 per cent of its current retail price, but without any guarantees that the car would be in a running, if not perfect condition.

So, when the car was delivered to his house he had every intention of gifting it to his daughter on her wedding day, which was then less than two weeks away. However, when he first started the car it would not idle; it only managed to maintain a sort of stumbling, “coughing”, and erratic idle accompanied by muffled backfires through the exhaust after it had warmed up somewhat. It was at that moment that he began to think he might have made a mistake to pay a fortune for this “loathsome” Lamborghini, especially since he could also not raise the engine speed to above around 2 000 RPM.

Long story short, though: by going through the documentation that had accompanied the car, the owner discovered an invoice from a dealer in exotic cars for a timing chain replacement when the car had completed just under 30 000 km. The value of the invoice is not important (few people would believe this job could cost that much, anyway), but the point is that not even an exotic supercar should require a timing chain replacement at such a low mileage.

The car’s owner also handed us a diagnostic report that listed only one trouble code, this code being P0014 - “Bank 1- Exhaust Camshaft Retard: SPECIFICATION NOT REACHED”. The report, which also came with the car’s documentation, was dated less than a week before the date on the invoice for the timing chain replacement, meaning that the two documents were almost certainly relating to the same issue. At this point, we should have simply declined the job, but we did not, so let’s look back at-

As soon as the customer left, we gathered to collect our thoughts and compare notes on what we knew about this or any other Lamborghini Gallardo. Collectively, it wasn't much, but we did know that the V10 engine in this car was designed by Audi specifically for use in the Gallardo model range. We also knew that starting in 2006, Audi began using this engine in the A8* model range.

*Not to be confused with the Audi R8 that uses a 5.2L V10 engine that differs from the V10 engine in the Gallardo in various ways, including firing order, piston/connecting rod design, crankshaft weight/length, and method of fuel injection: the engine in the Audi R8 used direct injection, while the engine in the Gallardo used port injection.

As a practical matter, our problem was this; we did not own, or have access to Lamborghini-specific diagnostic equipment and software. However, we spent some time speculating about the chances of the engine management calibrations on the Audi and Lamborghini versions of this engine being sufficiently similar that we could use our Audi-specific software.

We did not want to connect Audi-specific software or worse, generic software to this car in case we fried something. However, an internet search revealed that Lamborghini-specific software was vastly more expensive than we were willing to pay if we could get the answers we needed another way, so we set out to find out if Audi-specific software would work on the Lamborghini.

We hit on the idea of compiling a list of Lamborghini and Audi dealerships and then calling them, hoping that one or more would talk to us. After three days, we found a dealer in the United Kingdom who told us what we needed to know. According to their chief mechanic, the engine management calibrations were sufficiently similar* to extract most generic engine fault codes with our Audi-specific equipment.

*We knew that a) VW owned Lamborghini through their subsidiary Audi, and b) that the same engine was in service in both Lamborghini and Audi models. However, we were not sure if that would automatically translate into engine calibrations that were identical or even similar.

This information was a good start, but we needed confirmation, which we received the next day when an Audi-dealership in the USA told us they routinely extract generic engine fault codes from Lamborghini Gallardo's with Audi-specific software via a pass-through device because the Lamborghini-specific software was so expensive. As a result, Gallardo owners there get some diagnostics done cheaper at most Audi dealers than they do at Lamborghini dealers.

Thus, armed with the knowledge that we were unlikely to fry anything, we connected a laptop computer running Audi-specific software to the Lamborghini via a pass-through device. Then, by dint of fiddling with some settings, we managed to extract fault code P0014 - Bank 1 - "Exhaust Camshaft Retard: SPECIFICATION NOT REACHED”.

We did not expect this code after the car had had a timing chain replacement, but since there were several possible explanations for this code, we were not overly concerned at that point. For one thing, the people who replaced the timing chains might not have cleared the code, but we thought that was unlikely, although not impossible. One other possibility was that the technicians that replaced the four timing chains might have a) installed something wrong, or b) they might have somehow gotten the valve timing wrong by a tooth or two when they assembled the engine.

You might think that this would be easy to verify, but the problem was that the timing chains are located at the back of the engine, between the engine and the transmission, so the only way to physically check the valve timing was to remove the engine from the car and to dismantle the engine. This was the very last thing we wanted to do, not only because of the effort involved, but mainly because we had no idea how to get the engine out of the car, and doing something wrong at the wrong time could potentially be very expensive to repair. We had to do this diagnosis by removing or dismantling as few things as possible, so the diagnostician thought we might scope the problem, and here is-

We can skip over the details of the unsuccessful search for information on camshaft code setting parameters for this engine. Suffice to say that in the end, we assumed that since the engine management calibrations were similar to the Audi version of the engine, the camshaft code setting parameters would likely also be similar, if not identical. As a general principle, Audi engines with variable valve timing would set camshaft codes if the actual and desired positions of a camshaft differ by more than 10 degrees, and we were hoping that this would be the case for the Lamborghini version of this engine, as well.

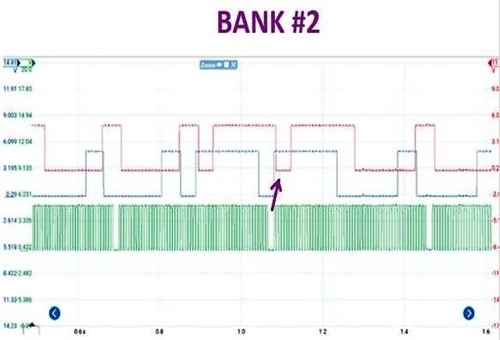

After a process of trial and much error, we finally divined the correct wires on bank one and the crankshaft position sensor to connect an oscilloscope to, and with the engine (barely) running, we managed to capture the traces below-

Image source: https://www.vehicleservicepros.com/service-repair/underhood/article/2one236508/dont-let-the-four-chains-scare-you

The object of this test was not to deduce or measure absolute values; the purpose was to verify that there was indeed a difference between the positions of the two exhaust camshafts at idle, so we repeated the test on bank 2. This is what we found-

Image source: https://www.vehicleservicepros.com/service-repair/underhood/article/2one236508/dont-let-the-four-chains-scare-you

The points that are arrowed in these traces show the difference in degrees of camshaft rotation in relation to the position of piston #1, as relayed by the crankshaft position sensor. However, in this case, the exhaust camshaft on bank 1 was both overly retarded and overly advanced. It was advanced relative to the exhaust camshaft on bank 2, and it was retarded relative to the intake camshaft on bank one because it appeared not to have returned to its base or rest position.

This made some kind of weird sense because if nothing else, it explained the backfiring through the exhaust. Thus, at this point, the problem could be due to a few reasons, including-

By this time, we were a week into the job, but we did learn a few things. We now knew that there was an actual problem on bank 1, and we knew that it was going to be tricky to repair. Together, these two things did not add up to much but still, we now knew more about the problem than we did a week ago.

Anyhow, we needed to verify whether (or not) the valve timing on bank 1 was actually off, but since we (somewhat unsurprisingly) could not get the bidirectional controls on an Audi-specific scan tool to work on the Lamborghini, we could not rotate the camshafts through their full range of motion to exclude or confirm an actuator failure or fault.

As a result, we were forced to a) rent a set of timing tools for the engine and b) buy a hugely expensive repair manual online to see how the tools worked. Long story short: when the timing tools arrived a few days later, we followed the instructions in the manual and somewhat unexpectedly, they slipped right into place, which definitively ruled out a problem with the actual valve timing. This development led us to consider -

Now we were dealing with two seemingly incompatible issues; on the one hand, the scope traces indicated a valve timing problem, but on the other hand, the fact that the valve timing tools slipped into place without any trouble proved that the engine was timed correctly.

Of course, damaged or severely worn cam lobes, stuck or broken valve lifters, or broken valve springs might very well explain both the misfires and the backfires, so we removed both valve covers to inspect the camshafts for damage. It turned out, however, that both camshafts on both banks were in perfect condition. There was plenty of fresh oil in evidence, and a simple check with a feeler gauge did not turn up issues with valve clearances, which ruled out issues with valve lifters, valve springs, and rocker arms.

As a result, we concluded that since this was a port-injected engine, it could be that an excessive build-up of carbon on the intake valves somehow interfered with the intake charge, which might produce poor combustion and perhaps, slight backfiring through the exhaust. As it turned out, however, we never discovered the cause of the backfiring.

The next thing we needed to check was the condition of the camshaft actuators, but since they were tight up against the firewall between the engine and passenger compartment and were, therefore, all but inaccessible without removing the engine from the car, we decided to take another tack.

We thought we might learn something if we tested the operation of the VVT oil control solenoids, both of which were just barely accessible. Upon testing, both solenoids showed current on one circuit when the ignition was switched on, and the current on both solenoids dropped away when the ignition was switched off. However, since the engine would not rev up to more than about 2 000 RPM, we could not test drive the car with a scan tool connected to see if the solenoids worked when the ECU commanded changes in valve timing.

Again, we did the next best thing, which was to remove both oil control solenoids to bench-test them. Out of the car, both solenoids showed similar resistance values, and both solenoids made audible "clicking" sounds when we applied power to them. As far as we could tell, both solenoids worked OK, but on a hunch, we thought we might swap them around to see if the problem moved to bank two. It did not, so we changed the solenoids back again.

At this point, the chief mechanic learned on an obscure technical forum that this particular Lamborghini model had two interchangeable plug-and-play ECUs and that in some cases, it was possible to confirm or eliminate some types of electrical issues by swapping them around. After some extensive searching, we found both ECUs, swapped them around, and nothing changed. The problem was still present on bank 1, so we swopped the ECUs back again, which brings us to-

By this time, this particularly loathsome Lamborghini was beginning to become a huge embarrassment to all who were involved with it. Worse, though, our failure to identify the problem in time meant that the customer could not give the car to his daughter on her wedding day, since the wedding had already happened during the preceding weekend.

Nonetheless, we were determined to find the underlying cause of the problem one way or another. Therefore, we had another meeting of the minds to discuss what we knew, but more importantly, to see if we could figure out a) what we were not seeing, b) what we were overlooking- which we obviously were.

This engine was, after all, just another internal combustion engine that needed the same things to work that any other internal combustion engine needs to work. Even though it was installed in a million-dollar supercar, this engine still needed fuel, cylinder compression, and an ignition source to run, as well as proper lubrication and efficient cooling, to continue running.

In this case, though, fuel, compression, and ignition were apparently not all present at the exact moment they were required but they were present nonetheless, since the engine ran, albeit poorly. Cooling was not an issue at this point, since we have not had it running for long enough for excessive heat to be a factor. This left us with lubrication, but since the engine ran without mechanical noises, we assumed that there was sufficient lubrication available at all points in the engine- and it was then that the proverbial penny dropped.

We were overlooking the fact that while the lubrication system supplies pressurised oil to the timing chain tensioners to maintain proper chain tension, the lubrication system also supplies pressurised oil to the variable valve timing system to, well, change the valve timing when commanded to by an ECU. So, to test our newly-developed hypothesis that we might be dealing with an oil pressure problem, we devised a rather radical experiment.

We would remove the oil control solenoid from bank 1, and start the engine to see if there was pressurised oil available at that point. We removed the solenoid, but to protect the car's paint, we draped many layers of old newsprint over the engine as a precaution to prevent oil from squirting all over the car. Then, we started the engine and let it run for about five seconds.

It turned out, however, that no oil squirted from the hole in the engine where the oil control solenoid lived. There was no oil on the newsprint, but to be 100 per cent sure, we repeated the experiment, but this time, we let the engine run for a few seconds longer. There was still no oil coming from the hole in the engine.

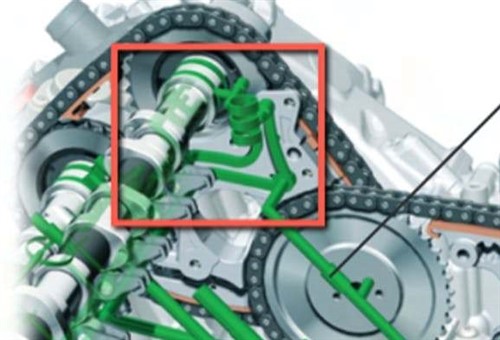

This discovery revealed the problem; for some unfathomable reason, there was a localised blockage in the oil circulation system that deprived the actuator on the exhaust camshaft on bank 1 of oil. Assuming that the oil circulation systems on the Audi and Lamborghini versions of the engine were the same, we consulted our hugely expensive repair manual to see if we could pinpoint the site of the blockage. This is what we found-

Image source: https://www.vehicleservicepros.com/service-repair/underhood/article/2one236508/dont-let-the-four-chains-scare-you

This diagram from the manual shows two separate oil channels for bank 1. The thick green lines at the bottom of the frame represent the flow path for oil to lubricate the camshafts, valve lifters, and rocker arms. The oil circuit at the top that runs through the red square supplies the chain tensioners and camshaft actuators on bank 1, which arrangement explained why the camshafts on bank one had plenty of oil, but the actuator did not have any.

We could not be absolutely sure about the exact site of the blockage without dismantling the engine, but as far as we could figure it out, the blockage had to have been in the area covered by the red square. More precisely though, the blockage had to be have been after the chain tensioner on the exhaust camshaft, but before the camshaft actuator, thus depriving the actuator of pressurised oil.

So, as a practical matter, the only thing that held the camshaft actuator in some sort of position was the unit’s built-in spring that helps to return the exhaust camshaft to its rest position. However, some of whatever blocked the oil channel must also have entered the actuator, and this likely prevented the actuator from fully returning to its rest position, which leaves us with this-

The customer was not exactly pleased that he could not give the car to his daughter on her wedding day, but on the other hand, he was rather impressed that we had managed to identify the problem without taking the car and/or engine apart.

At this point, the customer also shared with us the fact that he had contacted the dealer who had performed the timing chain replacement to get more details on why such a major procedure was performed on an engine that was for all practical purposes, still new. According to their records, the original owner had complained of a poor idle quality and a dramatic loss of power, so they did what they always did to cure this very common problem on this particular engine- they replaced all four timing chains, as well as all chain guides, sprockets, and tensioners with OEM parts.

However, when this did not cure the problem, they offered to find and fix the problem for what amounted to no cost to the original owner who declined the offer for reasons he did not share. Instead, and put the car into storage, which was where our customer found it several years later.

The only logical inference we could draw from this was that whatever caused the blockage must have been present in the engine when a) the car left the factory or b) during one of the three logbook services the car had had before the problem manifested. In any event, we declined the opportunity to find and clear the blockage because we did not have the experience, knowledge, technical information, and equipment that was required to do this job to factory standards.

Overall, one could ask if three experienced technicians really needed three weeks to diagnose what turned out to be a relatively simple, and what really should have been an obvious problem. Maybe not, but at the time, there was no doubt that we allowed ourselves to be intimidated by an engine that likely cost more than any of us earned in an entire year. Then again, wouldn’t you have been intimidated as well, even just a tiny bit?