Electric vehicles, or EVs for short, are often touted as the solution to many of the worlds’ problems, not the least of which is climate change and the general degradation of the environment. In fact, some major car manufacturers, most notably Ford, has largely abandoned further development of internal combustion technologies in favour of developing EVs, and while this may appeal to a large section of green-minded consumers, EVs, in general, face a very rocky road on the path to wide-spread adoption not only in Australia but also on a global scale.

Although electric power trains have largely matured as a technology, the problem is that much of the fanfare about EVs* derives from unrealistic projections on expected sales volumes of EVs and ill-considered bans and restrictions on fossil-fuelled vehicles by many of the world's major governments. However, for the purposes of this article, we will refrain from debating political issues/aspects and instead, focus on some of the practical, real-world issues that affect the global adoption of EVs. Before we get to some of the specifics, though, it might be useful to consider-

*Note that for the purposes of this article, the term “electric vehicle” excludes all types of hybrid technologies that use an internal combustion engine.

Since the early history of electric cars is long and convoluted, we will start this brief history lesson by saying that the first viable electric vehicle that saw extended service in the United States was a wagon capable of carrying six passengers. This wonder was developed by William Morrison between 1890 and 1891, and after several failed attempts, Morrison’s invention could eventually reach speeds of 23 km/h, albeit at ranges that varied from 15km to about 20km, depending on the loads carried.

At the time Morrison’s wagon began operating, there were already dozens of manufacturers in the US that made petrol and/or diesel power vehicles. However, since petrol and diesel fuels were scarce, expensive, and dangerous to transport over large distances at this time, electric vehicles soon became the norm, especially in towns and cities where their severely limited ranges did not present a major problem.

As a matter of fact, Samuel's Electric Carriage and Wagon Company operated a fleet of 12 electrically powered taxis in New York City in 1897, which was expanded to a fleet of 62 taxis by 1898, when the company was transformed into a new entity called the Electric Vehicle Company. In addition, by 1897, a fleet of electric taxis began service in London in Britain.

So while electric vehicles were mostly used by transport companies in the years up to 1912, interest in, and buyer uptake of, electric vehicles saw a huge upsurge among the general public when electricity became available in many, if not most private homes. The availability of domestic electricity obviated the need to use battery exchange services to keep an electrical vehicle on the road, and by the end of 1912, more than 38 per cent of personal vehicles registered in the United States were powered by batteries, while about 40 per cent were steam-powered. At this time, petrol and diesel-powered vehicles accounted for only 22 per cent of all vehicles in the United States.

In terms of numbers, there were a total of 33 842 electric vehicles in daily use in the United States by 1912, meaning that there were more electric vehicles in daily use in the United States than in all other markets combined. Nonetheless, the boom in electric vehicle sales started to decline in the late 1910s, when cheap and abundant crude oil was first discovered. Although the roll-out of the distribution network of refined fuels saw many delays, “turf wars”, and several hugely expensive and years-long lawsuits among suppliers and competitors, petroleum fuels largely displaced electricity as a power source in less than 15 years.

In practice, the availability of cheap and abundant liquid fuels had effectively killed off electric vehicles by the early 1920s. Nonetheless, several manufacturers of electric cars managed to remain in business until the late 1920s, and even into the early 1930s, and one such manufacturer, appropriately named “Elcar”, produced, and marketed the vehicle shown below until 1934.

Image source: https://www.peakpx.com/en/hd-wallpaper-desktop-khwbl

This particular Elcar model holds the dubious distinction that it was the first electric vehicle that earned its driver the first speeding ticket when the driver was caught exceeding 100 km/h on a public road, which brings us to-

As with the early history of electric vehicles, the period from about 1926 to 1960 when the Henney Motor Company introduced their version of a viable electric vehicle, called the Henney Kilowatt, into the US market, is equally convoluted and complicated.

This period saw the development of a great many electric vehicles, many of which never made it into production, or saw very small production volumes and as a result, we can skip over this period to save time. However, this period did see the development of effective controllers and other technologies such as efficient DC motors, and batteries that were somewhat more efficient than the run-of-the-mill lead-acid batteries that were available at the time.

Thus, in general terms, electric vehicle technology saw little to no significant advances from 1959/60 until 2004, when Elon Musk of Tesla fame started developing technologies that would make electric vehicles suitable for highway use. These developments included but were not limited to refining lithium-ion batteries and solid-state electronics to control and manage these batteries over a range that exceeded 300 km of continued driving at highway speeds.

It is perhaps worth mentioning the reaction of GM's Vice Chairman in 2009 when Tesla Roadster models began appearing on America's roads in significant numbers. Here is what he said at the time-

“All the geniuses here at General Motors kept saying lithium-ion technology is 10 years away, and Toyota agreed with us – and boom, along comes Tesla. So I said, 'How come some tiny little California startup, run by guys who know nothing about the car business, can do this, and we can't?” (Source: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/08/24/plugged-in)

In the real world though, much of General Motors' collective surprise at the fact that a "little startup" could produce highway-capable electric vehicles had to do with the machinations and corporate politics all major US manufacturers had been engaged in to defeat and subvert most of the CARB (California Air Resources Board) emissions regulations.

This period in the development of electric vehicles is particularly interesting, albeit convoluted. Essentially, US car manufacturers deliberately underfunded, under-advertised, and generally dragged their feet in developing electric vehicles to create the (false) impression among the public and regulators alike, that the general motoring public is really not interested in owning and operating electric vehicles, which brings us to-

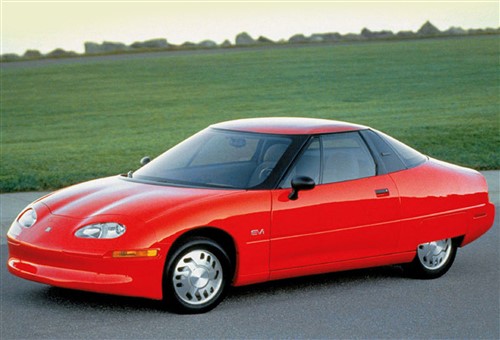

Image source: https://www.autocar.co.uk/slideshow/biggest-flops-automotive-history-1

Before we get to the specifics of why electric vehicles face a rocky road toward universal adoption, and especially in the Australian market, we should perhaps mention the first "mass-produced" electric vehicle- General Motor's EV1, an example of which is shown above.

Although this vehicle was reasonably successful as a technological experiment, it was in production for only three years, between 1996 and 1999, but saw a production run of only about 2 500 units. The first generation EV1s had lead-acid batteries that gave it a range of about 100 km, while the second generation EV1s used nickel-metal hydride batteries that extended the range somewhat, but at the expense of a shortened battery life and increased charging times.

Much had been written about the demise of the EV1, and while many commentators have put different political “spins” on this episode, GM itself had been remarkably reluctant to discuss the issue. Nonetheless, what is known is that GM did not want to develop the EV1 in the first place, because a) doing so would divert billions of dollars from their research and development efforts into new internal combustion technologies, and b), the CARB regulations compelled them and other manufacturers to develop zero-emission vehicles, which GM thought could not be done profitably.

Thus, being between the proverbial rock and a hard place, GM devised a plan to kill off the EV1. This plan involved making EV1s available to the public only via lease agreements, and then only in very small geographic areas. In practice, customers could never own their vehicles: at the end of the lease period, the vehicle had to be returned to the factory. Nobody* ever managed to keep their vehicles after the lease had expired, and nobody could ever lease a second vehicle.

* Except for one famous movie director, who managed to hide his EV1 from GM when they wanted it back. The details of how he did this are unclear, but this vehicle showed up in his collection of rare vehicles many years later.

By late 1999, GM had recovered all existing EV1s, and while the vast majority of EV1s was destroyed, GM did donate about 40 units to various US-based museums and research/training institutions, albeit with deactivated drive systems. As a point of interest, the Smithsonian Institution was the only museum in the US to receive a functional and drivable EV1, but only because they do not accept non-working examples of anything.

As a practical matter, there were no technical reasons why GM could not have used their EV1 as a platform to develop electric vehicle technologies further. Had they done so, they might have escaped bankruptcy in 2009, but that is perhaps a topic for another time. Nonetheless, the point of recounting the EV1 sage here is to show that Elon Musk is not the "father" of electric vehicle technology: while the Tesla models produced to date have been hugely successful, the fact is that these vehicles are largely built on technologies that predate even the first Tesla models, which brings us to-

Since limited space precludes even brief discussions of all the various technical issues and shortcomings that affect all electric vehicle models available today, we will instead focus on some of the issues that influence a potential buyer of an electric vehicle, one way, or the other. While some of these issues affect potential buyers of electric vehicles in Australia more than in other markets, all the issues we discuss here affect the buying decisions of potential buyers of electric vehicles in all markets, albeit to different degrees. Let us start with arguably the biggest obstacle to widespread adoption of electric vehicles in Australia, this obstacle being-

Although the average range of modern EVs is 340km, actual, achievable ranges depend on many factors, which include, but are not limited to the vehicle concerned, how the vehicle is used, the age and condition of the battery pack, as well as whether (or not) the vehicle is loaded or towing anything. Examples of this variability would be the 640 km range of the Mercedes EQS 450+ at the top end of the scale, and the 95 km range of the Smart EQ forfour, at the bottom end of the scale.

So while an average range of 340 km might not be much of a problem in Australia’s metropolitan areas where most of the charging stations are located, the long distances between charging points outside of these areas make it almost impossible to use an electric vehicle. This is greatly exacerbated by the fact that as of 2021, there were only about 3 000 charging stations spread out across the country. Below is a table showing how charging points are distributed across the country-

However, this table does not tell the whole story, because while there is little verifiable information available, the total numbers of charging stations in each jurisdiction are not broken down by type. Generally speaking, EV chargers come in different flavours, these being Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 chargers.

As a practical matter, Level 1 and Level 2 chargers use AC and depending on the actual charger and the vehicle being charged, charging times can vary from about 2 hours to about 5 hours or so. By way of contrast, Level 3 chargers use DC at very high currents, meaning that most electric vehicles can be charged from "empty" to "full" in about 15 to 20 minutes.

So based on the information in the table above, the problem becomes this; most road trips would not be possible with an electric vehicle. In fact, based on experiments by the authors of this article, it turns out that of the country's 15 most iconic road trips, only nine would be doable with an electric vehicle, and then only with an electric vehicle that has a range of 480 km, which excludes many of the EV models currently available in Australia. The details of these trips can be found here.

Of course, few people would buy an expensive EV just to see if they can complete an iconic route, but the fact is that the severely uneven distribution of charging stations in Australia makes it all but impossible to use EVs in areas outside of the big cities. By way of comparison, the state of California in the USA is about 19 times smaller than Australia, but it has about 78 000 public and shared charging stations, which brings us to-

According to this report issued by the Electric Vehicle Council, there were only 31 electric vehicle models for sale in Australia in August of 2021 although this number was expected to increase to 58 models by the end of 2022.

Moreover, also according to this report, only 8 688 EV models were sold in the first half of 2021, but it is not clear how many of these were Tesla models. There is some anecdotal evidence to show that Tesla sold at least 10 000 vehicles during 2021, but this is almost impossible to verify since Tesla is the only manufacturer of electric vehicles that does not publish sales figures on a country-by-country basis.

These sales figures compare poorly with those in other markets. For instance, in 2020, electric vehicles accounted for 10.7 per cent of all vehicle sales in the UK, while in Norway, electric vehicles accounted for 74 per cent of all vehicles sales in the same year.

More importantly, as of August 2021, there were only 14 electric vehicle models available in Australia for under $65 000. According to this report, this should be seen against the backdrop of the fact that a) in 2020/2021 the average price of conventional vehicles was only $28 000 and b), that the Federal Government does not offer buyers of electric vehicles any financial benefits or incentives.

For example, in markets like the US, both the federal government and state governments offer incentives like tax deductions and carbon credits, while in the Norwegian and other northern markets, governments have official policies and guidelines in place to keep the prices of electric vehicles on a par with those of comparable conventional vehicles.

Taken together, the high asking prices of electric vehicles and a lack of financial support represent a major disincentive for people to buy electric vehicles. In addition, while it is possible to realise savings in running costs of EVs compared to those of conventional vehicles, the EV would have to cover at least double the average trip total of about 12 000 km to realize a saving of less than $1000 over five years, which leaves us with this-

It would be fair to say that most people who buy electric vehicles do so because they care about the environment, but this statement comes with a caveat- this caveat being that in Australia, the fastest growth in EV adoption happens at the upper end of the price spectrum.

This is the end of the spectrum that makes it impossible for a large section of the motoring public to buy an EV, no matter how much they cared about the environment, but this situation might change when a second-hand market for EVs develops. For instance, NWS has recently started offering financial incentives to medium and large private fleets to switch to EVs in a move that is said to be aimed that kick-starting a used market in EVs, based on the assumption that private fleets usually replace their vehicles every three to five years.

While this report describes the EV policies of NSW as the most progressive in Australia, the fact is that unless the Federal Government takes drastic measures to increase the uptake of electric vehicles in Australia, the country will likely remain in thirty-second place (out of 36 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) in terms of electric vehicle sales/ownership for at least the next several years. In fact, only Mexico, Chile, and Turkey have lower EV sales than Australia, and all three of these countries are seen as emerging or developing markets. Thus, overall, the uptake of electric vehicles in Australia faces a long, hard, and rocky road to large-scale adoption by the motoring public.