We can (with a fair degree of confidence) say that we all remember the severe discombobulation we experienced when we realised that what we were taught in trade school did not quite equip us with what we needed to a) plan our first complex diagnostic procedure, and b) to implement and execute that complex procedure successfully. In the interest of fairness to trade schools though, it must be stated that while they do decent jobs of turning out reasonably competent mechanics, trade schools cannot be expected to teach apprentices things like intuition, confidence, or the ability to resist over-thinking relatively simple problems.

If you are an experienced technician, you will no doubt agree that if it were not for your intuition, you would not have solved some diagnostic conundrums as easily as you did. Some of us call this a “gut-feeling” or a “hunch” but regardless of what we call the instinctive knowledge that we are on either the right or wrong track, diagnostically speaking, we will all agree that this ability comes only after some years of working for our own accounts, so to speak.

Newcomers to the trade typically do not have this experience, so in this article, which is aimed at newly qualified mechanics and senior apprentices, we will discuss two case studies of diagnostic processes that went wrong purely because the responsible technicians did not understand the nature of the simple problems they were dealing with. Before we get to specifics though, let us start with discussing-

As an employer, this writer has often observed the bewildered look on a newly qualified mechanic’s face when the newcomer realises that he does not know where and/or to begin the process of diagnosing a problem. In many, if not most such cases, confused mechanics tend to overthink the problem at hand, in the sense that they try to relate symptoms to causes that do not apply to the observed symptoms or reported customer concerns.

However, it is not the intention of this article to belittle newcomers’ sense of confusion or lack of advanced diagnostic skill; far from it, seeing that even the most experienced technicians among us sometimes experience moments of self-doubt when our well-thought-out diagnostic processes fail to deliver the results we expected. So what does this revelation mean to the average newly qualified mechanic?

It simply means this- it is easy to make a mistake or to be led down a rabbit hole due to tunnel vision, or a failure to reduce the problem to its simplest form. To illustrate the importance of defining a problem, or reducing it to its simplest form, we will look at two examples from this writer's workshop of problems that could have been resolved within minutes had the responsible but newly qualified technicians not over thought the problem. Let us start with-

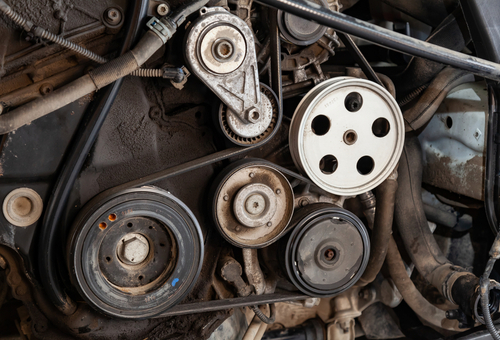

Note that this image is not of a BMW engine- it is purely intended to be illustrative. Nonetheless, this particular X5 belonged to a customer who occasionally brought the vehicle to us after it had passed out of warranty several years before. Because of this, we did not know the vehicle well and did not have a solid relationship with the customer.

Long story short, the customer arrived one day complaining that the vehicle had started to run a bit hotter than normal at low speeds, but that it had not seriously overheated in the three weeks or so since he first noticed the heat gauge rising to above normal. The service advisor wrote up the repair order and handed the vehicle to a young technician that had joined us two weeks earlier directly after completing his training at a local Ford dealership.

It would be easy, if not tempting to blame what followed on his Ford training. However, that would be unfair to the people who had trained him, especially since the chief mechanic had (quite correctly) forbidden the hapless young technician from undertaking a test drive because of the possibility that the X5 could conceivably suffer fatal overheating during the test drive. Here is how this sorry saga played out-

Being deprived of what the technician later called his “primary weapon” and “principal diagnostic aid” aka, the test drive, he did the next best thing, which was to run a full diagnostic scan, which turned up nothing apart from some recent freeze frame data that showed some coolant temperature readings that were decidedly above normal at low engine speeds. There were no misfire codes stored, and fuel trims were all normal. There was no air and fuel metering, nor any emission control codes present, the radiator fan speeds were normal when they were checked via bidirectional controls, and an exhaust backpressure measurement showed that the exhaust system was not restricted.

The technician then ran a chemical block test to check for the presence of exhaust gas in the engine coolant, which turned out negative thus ruling out a damaged cylinder head gasket, and this is where things became undone. At this point, the technician should have realised that he was dealing with a coolant circulation problem, but because he probably thought that BMW X5 cooling systems were somehow different from Ford cooling systems, he was unable to reduce the problem to its simplest form.

With the perfect vision that hindsight brings, we know that any coolant system is only effective if certain preconditions obtain. To wit-, the cooling system is filled to its full capacity; b) the coolant can circulate freely throughout the system, c) the coolant system can maintain its design pressure, and, d) that the coolant pump can effectively pump the coolant around the engine. However, the technician did not have these insights because he was-

There is much else to relate but in the interests of brevity, we can say that by the time the chief mechanic checked on the young technician’s progress, he found the following-

We won’t go into the finer details of who said what to whom at this point: suffice to say that while inspecting the carnage, the chief mechanic noticed a) that the ribs on the drive belt were severely worn, and b) that the grooves in the water pump’s pulley were worn shiny right down to their roots.

Thus, the inescapable conclusion was that had the technician taken one minute to inspect the drive belt when he turned up no trouble codes he would have recognised that the drive belt had been slipping on the water pump’s pulley, which was the direct cause of the poor coolant circulation and concomitant overheating under some operating conditions, which brings us to-

Again, we will gloss over the finer details, but the failure of the young technician to recognise and implement a simple solution to a straightforward problem resulted in not only the unnecessary replacement of a perfectly good radiator but also in having to explain to the customer why we were not charging him for the very expensive new radiator and fan motor.

There is no telling exactly what went through the customer’s mind while he listened to the chief mechanic’s explanation. He simply listened and left without saying a word after paying for the new drive belt, tensioner, and water pump pulley, and we have not seen him or heard from him in the two years or so since the incident occurred.

We have probably lost this customer forever and we can’t blame him for staying away, since there was plenty of blame to go around, after all. Nonetheless, this episode also forced us to re-evaluate our systems and procedures, and specifically in terms of how repair orders are written, and in making sure that everybody understood the problems they were dealing with.

The young technician is still with us, but he was reassigned to be our resident and highly skilled diagnostician’s understudy as a means of developing his diagnostic skills. Although he still has a long way to go before regaining our full trust, he has shown a remarkable degree of personal growth and development in terms of his approach to diagnostics- and especially in his ability to reduce problems to their simplest forms before starting to pull cars to pieces because of his propensity to overthink simple issues.

While this story had a relatively happy conclusion, another instance of a technician (that was considerably more experienced than the unfortunate young technician) overlooking a simple cause of brake failure on a 1976 Mercedes turned out less well. Thus, let us consider the case of the-

The story revolves around a simple problem; a long-time customer brought his much-loved pre-ABS 1976 Mercedes 450SL in and complained that the brake pedal had a "spongy" feel and that the brakes did not "work properly". He added that he had performed a brake pad and rotor replacement a week before, and since the existing brake fluid “looked dirty”, he replaced the brake fluid by purging the system with a vacuum pump of his own devising.

The service advisor wrote up the repair order, noting that the customer had replaced the brake fluid, and handed the job off to a mid-level technician, which is another way of saying that he did not want to bother senior technicians with a simple job, and did not trust any of the apprentices or junior mechanics to do it right.

Whatever the service writer’s motivation was is not relevant here; what is relevant is that the technician who took on the job instantly diagnosed a failed master cylinder as the cause of the poor brake performance. This diagnosis was made without taking brake pressure readings at the wheels, or removing and stripping down the master cylinder to inspect it for signs of excessive wear, damage, and/or corrosion. Thus, a new OEM-equivalent brake master cylinder was ordered.

However, it turned out that the “spongy” brake pedal persisted after the master cylinder replacement, so instead of inspecting the brake system for signs of fluid leaks and/or damaged brake lines, the responsible technician merely continued to pump litres of brake fluid through the system in attempts to dislodge the “air bubble” he was certain was causing the problem.

Again, with the perfect vision of hindsight, it would be easy to say what the technician should have done at this point, given that even high-end pre-ABS brake systems are ridiculously simple and uncomplicated. For instance, instead of blanking off the brake system at different points in the system to isolate the problem, tunnel vision caused by an imaginary air bubble rendered the technician unable to recognise the nature of the problem.

So, what was the nature of the problem? Simply this- in the absence of leaks in the system, and given that the master cylinder was new, the two most likely causes of a spongy brake pedal on this particular brake system are excessive compressibility of the brake fluid, or far more likely, an increase in the volume of the system when pressure is applied. The latter possibility would have the effect of absorbing some pressure, thereby creating the “spongy” brake pedal feel. A typical example of such a condition would be a damaged flexible brake line that balloons under pressure.

For reasons that are still not entirely clear, the responsible technician did not consider these possibilities, which resulted in a crash that caused considerable damage to the car when the brakes on the pristine 450SL failed almost completely during a test drive- a test drive the technician undertook “to see if the air bubble was still there”.

This accident caused not only great embarrassment but also financial implications since the damage to the vehicle had to be made good. We will again gloss over the details of who said what to whom, but a subsequent inspection revealed that a flexible brake line had failed, thus causing the brake failure. In light of the ill-advised test drive, we had no choice but to let the responsible technician go, even though the Mercedes’ owner later recognised that he might have damaged the brake line when he’d clamped a pair of vice-grips over it to prevent fluid loss during his initial attempts to correct the “spongy” brake pedal.

Despite this admission by the vehicles’ owner, the responsible technician (who now works in the fast-food industry) should have detected the damaged hose had he reduced the problem to its simplest form, which was the brake system’s failure or inability to maintain applied pressures, which leaves us with this-

While it would be unreasonable to state that a) all problems have simple causes, and b), that all simple causes have simple remedies, it is nevertheless true that many, if not most misdiagnoses and unsuccessful repair attempts stem directly from faulty premises, and/or invalid conclusions that are almost always based on faulty observations and the poor interpretation of symptoms.

It is also true that even experienced and highly skilled technicians sometimes get it wrong, but despite that, there are valuable lessons for the inexperienced among us in the two case studies discussed here. The first is always to start a diagnostic process by looking at the simplest possible causes first, and the second is to devise diagnostic strategies that address all the observed symptoms, as opposed to manipulating symptoms to fit preconceived diagnostic processes.

Reducing even complex problems to their simplest form is the only way to devise a diagnsotic process that addresses all observed symptoms, which is in its turn, still the most efficient way to diagnose and resolve problems and issues on vehicles and/or systems that may be unfamiliar to you.