A US-based motoring journalist once made the observation that rear-ending each other remained American drivers’ favourite method of bending sheet metal, which observation is both apt and ironic, at the same time. It is apt because rear-end collisions caused nearly 3 million injuries to vehicle occupants in the USA between 2016 and 2020, and it is ironic because AEB (Automatic Emergency Braking) systems have been fitted to millions of light vehicles in the US automotive market since 2015.

So, given that the primary reason why AEB braking systems were invented was to prevent or reduce the number of car accidents in general, and rear-end collisions in particular, this report shows that in 2021, rear-end crashes accounted for just more than 50 per cent of all car crashes in Australia. Of course, since we do not have a car manufacturing industry anymore, there is no easily verifiable information available on how many vehicles on our roads are fitted with AEB systems, since we import most of our light vehicles from Japan (27.5%), Thailand (22.6%), Germany (9.8%) and Korea (8.1%). So why is this important, to us, as mechanics and technicians?

There are several reasons why this is important to us as mechanics, and in this article, we discuss some of those reasons as well as look at what we can do to improve our customer’s chances of surviving an accident when the AEB systems on their vehicles don’t work when they are needed the most. Before we get to specifics, though, let us look at-

The short answer is that it is not at all clear how many vehicles on our roads are fitted with AEB systems. However, it would be reasonable to say that since (nearly) all the cars on our roads are imported from markets that also supply the US and European markets, the vast majority of cars that are involved in rear-end collisions in Australia are fitted with some form of AEB system.

Having said the above, it should also be stated that all major car manufacturers in the USA have entered into voluntary agreements with regulatory authorities there to equip most of their products with AEB systems by 2022. This commitment will likely be converted into a legal mandate soon, but for the moment, there are no standards in force that define the minimum operating standards for AEB systems- not in the US or European markets, or anywhere else, for that matter.

Despite the lack of minimum standards that define operating parameters and other things like common names for systems* that do the same thing(s), however, the Federal Government has recently issued the following announcement-

“The Federal Government has made it a legal requirement for newly introduced light passenger and commercial vehicles (including utes and vans with a GVM of 3.5 tonnes or less) to have Autonomous Emergency Braking technology as early as 2023.”

This announcement goes on to say that (paraphrased) “…. the laws will be enforced progressively, and will initially only apply to new models introduced to the local market from March 2023. After March 2025, all new passenger and light commercial vehicles sold will need to be equipped with vehicle-to-vehicle AEB. Vehicle-to-pedestrian AEB will then also be mandated on newly introduced models from August 2024, before applying to all new vehicles [sold locally] from August 2026.”

So, what’s the problem you may ask? You may well ask because a) the term “Autonomous Emergency Braking” means different things to different people, and b) nobody knows exactly what they are getting* when they pay for a vehicle with an AEB system. More to the point, though; we, as mechanics and technicians, often labour under the misconception that AEB systems always stop vehicles before accidents occur when in fact, most AEB systems don’t work at all under some circumstances.

*See the end of this article for the (current) list of the names different car manufacturers use to describe the AEB systems on their products. Note, though, that in most cases, there is no obvious link between the grandiose (fancy) names car manufacturers use to describe their versions of AEB and the functionality of the AEB system on any given model.

We need not delve into the role that car manufacturers’ marketing departments play in naming ADAS systems, but from our perspective as mechanics and technicians, we do need to pay attention to the details of the four broad categories of AEB system functionality that are in current use, these being-

Low-speed AEB

As the term, “low-speed” suggests, these systems generally only work at speeds below about 80 km/h, and their function is to prevent accidents in places like parking lots or slow-moving city traffic. Note that these systems will not work at high speeds, or in conditions where the vehicle’s road speed exceeds about 80 km/h

High-speed AEB

In theory, “high-speed” AEB systems will work at road speeds above about 80 km/h since these systems use radar transponders and other devices that can “see” further along the vehicle’s direction of travel than those of low-speed systems.

Note, though, that there is no requirement that a high-speed AEB system must bring a vehicle to a full stop autonomously within a given distance. While some high-end systems can, and do bring a vehicle to a full stop, the only actual and (voluntary) requirement is that the system “scrub” about 10 per cent of a vehicle’s speed before a collision occurs. In most, if not many mid-level vehicles, however, high-speed AEB systems do not work at all under some circumstances.

Of course, some AEB systems greatly outperform others, but we will discuss this issue in more detail in a following section of this article.

Reverse AEB

As the term “reverse AEB” suggests, these systems only operate when the vehicle is in reverse, and moving at speeds that generally do not exceed about 30 km/h. The function of these systems is to prevent or mitigate accidents between vehicles and obstacles in driveways and parking lots.

AEB systems that detect pedestrians and cyclists

Although there are AEB systems that can sometimes detect pedestrians and (motor) cyclists, in addition to detecting other vehicles and major obstacles, these systems are currently only available on a handful of very high-end vehicles. However, these systems do not always detect pedestrians, and even when they do, they do not always manage to prevent collisions with pedestrians.

So, there we have it; the current state of AEB technology in vehicles on our roads. While this may be news to some readers, it is worth pointing out that many, if not most car owners are under the false impression that the AEB systems on their vehicles will somehow magically save them from getting into crashes because the “brakes engage automatically in emergency situations”. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In the interest of fairness, though, it must be stated that AEB systems have saved many lives, and prevented many potentially fatal injuries in mitigated rear-end collisions all over the world.

Nonetheless, this writer has engaged with many customers who stated that the AEB system in their vehicles was either not working, or not working as it should, based on their experiences(s) of their vehicles not braking automatically when they (the car owners) thought the brakes should have engaged automatically. In many cases, these conversations revolved around near misses and close calls that occurred in intersections, when oncoming vehicles were turning right without waiting for sufficient clearance between themselves, and vehicles carrying straight on through the intersection.

It might be tempting to say that such observations made by sometimes-inexperienced drivers are subjective, but the high incidence of so-called T-bone crashes in intersections argues otherwise. In fact, recent tests by the AAA (American Automobile Association) that were performed under near-real-world conditions* eloquently agree with many car owners that the AEB systems in their vehicles not only have serious limitations, but that, in fact, many AEB systems do not work at all under some conditions.

* This research report and its findings should be required reading for all mechanics and technicians who have ever attempted to diagnose an AEB system that did not work as expected but found no obvious faults.

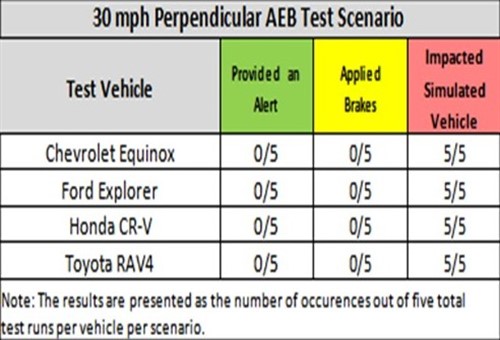

You may be surprised to learn that some AEB systems don’t work under some circumstances, but consider the table below-

Image source: https://newsroom.aaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Research-Report-2022-AEB-Evaluation-FINAL-9-26-22.pdf

The late-model vehicles listed in this table are common on our roads, and each was subjected to a series of five test runs at a simulated vehicle at different speeds to test the operation of their AEB systems. It is worth noting that the simulated vehicle had the same radar reflectivity as a real vehicle, and all tests were performed at, or below the speed limits that generally apply to inner-city roads- albeit American inner-city roads.

Nonetheless, American speed limits in inner cities are directly comparable to our speed limits in similar areas, so the test results shown here apply directly to similar late-model vehicles on our roads.

As a practical matter, this test simulated traffic flows through a typical 4-way intersection where some vehicles pass through the intersection when the traffic lights were on green, while other traffic turned 90 degrees to the left in front of traffic passing straight on through the intersection. The only difference is that here, the traffic turning 90 degrees in front of oncoming traffic would turn to the right.

NOTE: In this test, the simulated vehicle was towed by another vehicle, but at a distance that put it out of possible range of the radar transponders of the vehicle being tested, meaning that the test results are not influenced by radar transponders being confused by two simultaneous targets.

The test results shown here are illuminating, to say the least, because at no point during each of the five test runs per vehicle did the AEB systems on the test vehicles detect the simulated vehicle passing right in front of them. Worse, though, the simulated vehicle passed in front of the oncoming test vehicles at the same distance that a normal vehicle would pass in front of real oncoming traffic in a real-world intersection

Note that the table shows that a) none of the AEB systems on the test vehicles gave a warning of an impending collision, and b) none of the AEB systems on the test vehicles activated the brakes at all, resulting in each of the test vehicles colliding with the simulated vehicle five times out of five test runs.

Of course, this test used only four late-model mid-level vehicles, so it is entirely possible that a larger number of vehicles that is more representative of the national car parc would have yielded different results. Then again, from our perspective as mechanics and technicians, there is no reason to believe that the AEB systems on all of the other mid-level vehicles on our roads would have detected the simulated vehicle in the same kind of test.

We need not delve into the possible or likely reasons why the test vehicles failed to detect the simulated vehicle in time to prevent a collision, beyond saying that the most likely reason is the limited field of view of the radar transponders that underpin AEM technology. The current generation of radar transponders was designed to serve adaptive cruise control systems; in these systems, the radar transponder can “lock” onto a target that is dead ahead (or close to dead ahead) of the following vehicle.

Therefore, the time it takes for a vehicle to move perpendicularly past a radar transponder that was designed for a different purpose, i.e., adaptive cruise control, may not be sufficient for the radar transponder in an oncoming vehicle to activate the oncoming vehicle’s AEB system, which begs the question of-

Indeed; what do we tell a customer who has just barely missed being in a potentially serious accident because the AEB system in his late-model vehicle failed to detect a vehicle crossing in front of them in an intersection, and now wants us to find out why the system failed to work as expected?

Well, we could say that we will "take a look", but this is often a bad idea because many customers will simply not believe you when you say you could not find anything wrong. We could also say that the AEB system in the particular vehicle was not designed to work in the exact conditions the rattled car owner was in, but that only works when we know exactly what a car manufacturer meant when they said that the vehicle was equipped with some form of braking assist system or capability. Of course, we often don’t know what the car’s manufacturer meant unless we look it up.

None of us can be expected to keep up with how manufacturers name the various ADAS systems* in their products, which is why several international regulatory bodies are now pushing for regulations that will compel car manufacturers to give systems that do the same thing the same name.

*See the current list of names that apply to AEB systems at the end of this article.

However, until that happens, the only thing we can realistically say to customers is this-

In this context, “normal” would entail researching the exact capabilities of the AEB system in the vehicle. As described elsewhere, AEB systems are not created equal, but car manufacturers typically go to at least some trouble to publish this information in the vehicle user manuals that come with all new vehicles.

While they do this to educate the buyer of the vehicle on the capabilities of the AEB system, they also do it to escape liability claims when their product gets into an accident that the driver thought would not happen because the "brakes would engage automatically in emergency situations”.

So, while information about the capabilities of a vehicle’s AEB system is available to buyers of new or used late-model vehicles, this writer has found over many years that very few owners of new cars ever actually read the vehicle's user manual. This being the case, it falls to us as mechanics and technicians to educate our customers, especially about the fact that what they thought the AEB system in their vehicles could do, might not happen because the AEB system was not meant to do it, i.e., always stop the vehicle autonomously in all emergencies.

On a practical level, the best thing we could do for our customers is to help them manage their expectations regarding what AEB and other advanced ADAS systems can do, and cannot do since distracted driving is arguably the biggest cause of traffic accidents, and especially rear-end collisions in Australia. For example, BMW states in their user manuals that ABS brakes cannot overcome the laws of physics, and the same thing is true for AEB and other advanced ADAS systems not only in BMW vehicles but also in all other vehicle makes and models.

With the above in mind, it perhaps worth comparing what the AEB systems in the AAA test vehicles were called with their complete failures in some situations-

Based on these designations, it would be reasonable to assume that the term “Toyota Sensing” means nothing to the average car buyer because it is not at all clear what exactly the vehicle or system is supposed to “sense”. Moreover, Ford’s “Pre-Collision Assist with Automatic Emergency Braking” might be seen as misleading, since it could create the impression in the mind of an average car buyer that the AEB system will assist in avoiding or preventing accidents with obstacles, which it emphatically does not do in some situations.

Nonetheless, to ensure that the AEB systems on the test vehicles were fully functional, the test vehicles were obtained from dealerships, and serviced by the same dealerships according to manufacturer-specific procedures, which leaves us with just-

To help you educate your customers on the capabilities (or lack of capabilities, as the case may be) of modern AEB systems, this writer has compiled this list of what car manufacturers call their versions of AEB systems based on publically available information.

Be aware, though, that not all manufacturers listed here publish full details of what their AEB systems can and cannot do in vehicle user manuals. Therefore, this writer strongly recommends that you consult OEM-level service information about these systems if you have to answer your customer's questions about these systems, especially with regard to the range of minimum and maximum speeds at which an AEB system will work, or not, as the case may be.