This writer was recently invited to consult on the case of a two-year-old 7-Series BMW whose radar-based blind-spot monitoring system would not stay calibrated. We will discuss the details of the problem and its solution a bit later on, but in short, several attempts by this writer (spread over ten days) to calibrate the system, and multiple subsequent attempts by a BMW dealership failed to keep the system calibrated and working for more than two days at a time.

In the end, an expert collision repairer found the problem in under an hour, although the actual repair took more than a week. However, what this writer learned about how new cars are designed and constructed during the process of repairing the vehicle was a revelation, and in this article, we will discuss some of what this writer learned, as well as look at some of the problems collision repairers encounter while repairing accident damage on new cars.

On the face of it, it might not be apparent that how new cars are constructed affect much of the routine maintenance and repairs we do as mechanics. However, in many cases, issues like persistent uneven tyre wear, difficulties in calibrating steering angle sensors or other ADAS features stem directly from either poorly performed accident repairs, or worse, from accident repairs that should not have been performed in the first place. Before we get to specifics though, let us state-

In the interests of brevity, let’s just say that the vehicle belonged to an acquaintance of this writer who had operated a large collision repair business for many years. However, this acquaintance retired from high-level collision repairs in the late 1980s for health reasons but to keep himself busy, he started a paint-less dent removal service, specializing in repairing hail damage and other minor body damage that did not involve painting and/or refinishing work.

This business was hugely successful, so when the acquaintance retired a second time, he treated himself to a new 7-Series BMW of which he was inordinately fond. Sadly, though, one day while he was in hurry to be somewhere, he forgot about the two large concrete garden gnomes his wife had installed next to the driveway, and he reversed into one of them when he turned his BMW around in the driveway.

According to the vehicle’s owner, the collision with the garden gnome had not only fractured the rear bumper but also damaged the bumper stiffener (aka impact absorber carrier) behind the bumper. This is the point in the story where things get complicated, but suffice it to say that since the acquaintance used to be a body repairer, he thought it would be a simple enough matter to simply-

- all without involving his insurance carrier to forestall the possibility of an increase in his premiums.

Long story short; the new parts were sourced from a local BMW dealership, and while removing the damaged bumper stiffener was easy enough, it turned out that the bolt holes in the replacement part did not correspond as closely to the holes in the car’s bodywork as the acquaintance would have liked. It was not like the holes were off by much- they were decidedly off, but just enough to prevent the bolts from passing freely into the holes in the car’s body.

Thus, concluding that the new bumper stiffener was somehow not up to specification, he exchanged the suspect part for a replacement, which had the same problem. Comparing the second replacement with the first showed that they were identical in all respects, including the placement of the bolt holes, so if the bolt holes did not align, the problem must be with the car.

However, the damage to the original bumper stiffener was so slight that it seemed highly unlikely that the car's chassis would have sustained damage, and since there was no visible damage or even evidence of an impact on the car's body, the acquaintance discounted this possibility altogether. Therefore, to resolve the matter, the acquaintance simply slotted the holes on the stiffener a bit on both sides, had the new parts painted and reassembled the car, which brings to-

This writer enters the story at this point, so when the acquaintance invited this writer to calibrate the blind spot monitoring system, an initial inspection of the vehicle showed that there was something off about the way the rear bumper sat on the car. It was not something obvious or egregious; it was just that the rear bumper appeared to be offset slightly towards the left, and while this writer initially thought this was due to some trick of the light in the workshop, the bumper was later shown to be offset by nearly 3mm.

Nonetheless, at the time, the first calibration attempt at calibrating the blind spot monitoring system went off without trouble of any kind, and a full scan of the vehicle did not turn up any fault codes. All the ADAS systems on the car appeared to be in perfect working order, and a long-ish test drive through town after the calibration also failed to turn up any fault codes. The acquaintance paid the invoice and left a very happy customer.

However, the acquaintance brought the car back late the next day, complaining that the rearview camera and park distance control system were not working- as evidenced by the fact that the reverse display screen remained blank when selecting reverse gear. Sure enough, a scan with a BMW-specific scan tool turned up fault codes-

The acquaintance also mentioned that it seemed that the blind spot monitoring system was also not working, since the small flashing warning lights in the mirrors no longer came on as they used to. Strangely, though, there were no fault codes relating to the blind spot monitoring system.

This all seemed very strange, but on a hunch, this writer cleared the fault codes, which brought the reverse camera and park distance control system back to life. Since the lane departure warning and blind-spot monitoring systems worked with the same radar transponders, this writer also thought it might be a good idea to recalibrate the blind spot monitoring system. This procedure went off without a hitch (again), and a subsequent test drive through town and on the highway showed that the blind spot monitoring system was working- again.

Sadly, though, this pattern repeated itself several times over the next week or so. The acquaintance would bring the car back every second day, this writer would find the same trouble codes every time, and he would resolve them in the same way, but when this happened for the fourth time, this writer became convinced that the acquaintance must have done something wrong or perhaps overlooked something when he disassembled/repaired/reassembled the car.

Thus, to forestall the fifth episode, this writer referred the acquaintance to a BMW dealership to have a fresh look at the problem since diagnosing issues that arise from poorly executed body repairs fell outside of his area of expertise. Here is-

Image source: https://www.bavarianmw.com/images/books/3584/3/page.h90.gif

This image shows the location of the two radar transponders that serve both the lane keep assist and blind-spot monitoring systems on the acquaintance's car.

During subsequent conversations with the technician at the BMW dealership that was involved with this vehicle, there was nothing obviously wrong with either the vehicle or the DIY repair. The technician said he had removed the plastic bumper, and checked the positions and orientation of the radar transponders, which seemed to be positioned correctly. Next, he checked the inside of the bumper for the presence of stickers, labels, or dirt that could interfere with the operation of the radar transponders, but the inside of the bumper was clear and free of obstacles. Next, he checked the thickness of the paint on the bumper, but this was within specifications.

He did notice that the bolt holes in the bumper were slightly slotted, but since the radar transponders were positioned correctly, he was not overly concerned about the modified holes. He also noted that the plastic bumper was more difficult to remove and fit than he was used to seeing, but since all the fasteners and clips engaged, he did not think much of the fact that he had to struggle to engage some clips, because that happens sometimes. Lastly, he noted that the bumper seemed to be somewhat offset to the left, but he did not think that it was important, since this was not the first time he saw misaligned body panels and bumpers on a late-model BMW.

Thus, since he was satisfied that there was nothing wrong with the DIY body repair, the BMW found the same trouble codes this writer did, and also resolved them in the same way. However, the customer was back at the dealership less than two days later, complaining about the reverse camera and blind-spot monitoring systems again not working. The dealership resolved the issue again, but after another day or so, the acquaintance was back at the dealership complaining about the same things- again. This rinse-and-repeat procedure happened twice more, at which point the dealership referred the vehicle to a BMW- accredited body repairer on the assumption that the collision with the garden gnome must have caused some structural damage to the vehicle although there was no visible evidence of such damage. Here is-

As it turned out, the body repairer was one with which this writer has had a long and productive relationship, which is no doubt why the body repairer invited this writer to visit his premises to discuss the problem BMW.

When this writer arrived at the body repairer’s premises, he found the BMW clamped in a hugely complicated jig that supported the vehicle at multiple (padded) points. The rear bumper, as well as the wheels, was removed, and the chassis rested on supports that the body repairer explained were specific to this particular model. The most interesting thing was, however, that this jig sported several touch screens, all of which showed numbers in red, which the body repairer said told him that the car's rear end was misaligned by almost 3mm with respect to the car's longitudinal centre line.

We can skip over most of what else the body repairer said, but the gist of it was that the bumper stiffener was a structural component that was bolted onto the car during the assembly process, but while the body shell was clamped in a jig that was designed to “straighten out” the body shell. At this point, the body repairer and two of his technicians made some adjustments to the jig, and as if by magic, all the numbers on all the touch screens turned green. The body repairer then said that the vehicle was now "straightened out" and that a new OEM bumper stiffener would now fit perfectly without the need to modify the bolt holes.

Sadly, though, the repair was not as simple as bolting on a new bumper stiffener. The problem was that since the car had a) not been clamped in the correct jig when the new bumper stiffener was installed, and b) the vehicle had been driven while it was seriously "crooked", there was no telling if, and by how much, other structural components and critical joints had been affected.

According to the body repairer, the only way to ascertain this would be to take much of the rear end of the car apart to make sure some other critical measurements were within OEM specifications. The body repairer added that depending on which measurements were out of spec, it may or may not be possible to repair the vehicle to OEM standards.

When this writer expressed doubts that a slightly damaged bumper stiffener could cause that much structural damage, the body repairer replied that this would not have happened twenty years ago but since new cars are largely stuck together with glue nowadays, there is no telling what might happen even during insignificant fender benders. At this point, the body repairer launched into a long explanation (some would say a lamentation) of-

We can skip over much of the details of specific body repairs as related by the body repairer, but to keep things on track, we can list a few of the most important developments in the design and construction of new cars as they were related to this writer by the body repairer.

Up to about 20 or so years ago, car bodies were largely made of the same grade of steel, but since then, many manufacturers have begun using both high strength and ultra high strength steels to fabricate load-bearing and/or structural parts. This increased the overall rigidity of body shells while reducing weight at the same time, but at a practical level, these materials presented body repairers with serious problems.

For one thing, body repairers had no idea which parts were made from mild steel, and which were made from some exotic high strength steel since car manufacturers did not label individual parts. Moreover, while conventional welding methods did not affect the strength of mild steel much, the heat of conventional welding methods all but destroyed the structural strength of high strength steel around welds made during body repairs.

In practice, this affected several built-in structural features such as crumple zones negatively. Worse, though, since many, if not most car manufacturers did not provide proper repair instructions, many body repairers simply relied on past knowledge and experience to repair collision damage- even when OEM repair procedures were available.

In practice though, most, if not all body repairers began to construct their own lists of HSS and UHS steel parts and largely relied on shared knowledge to develop best industry practices to repair vehicles that contain large numbers of HSS components safely.

In a process that is largely analogous to how we learned about OBD II systems, body repairers were forced to retrain extensively after car manufacturers recently began providing proper mapping and/or labelling of individual HSS and UHS steel parts that go into car body shells. Provided body repairers are willing to pay for expensive subscriptions to third party vendors of body repair information, updated repair procedures are available today, but the bigger problem involves the use of-

As if dealing with UHS steels is not enough, many parts in modern body shells are made from exotic materials that incorporate a high percentage of boron and other very hard metals. So, while knowing which part contains boron or some other hard material is one thing, detaching such a part from damaged vehicle is another matter entirely.

Normal drill bits are useless to remove spot welds from such materials, and while appropriate drill bits are available, they are hugely expensive and even the best available drill bits cannot drill out more than two or three spot welds before breaking or melting. Moreover, normal abrasive cutting discs do not work on solid welds on boron-containing parts, so body repairers have to invest in hugely expensive specialized cutting equipment to work with these types of parts.

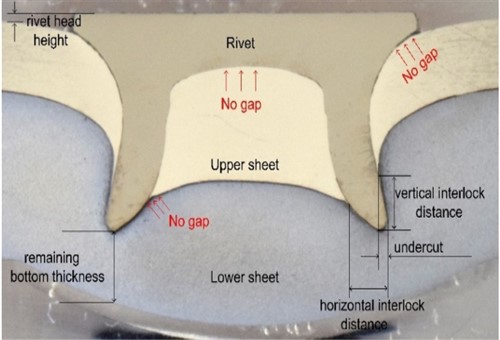

Then there is the problem with self-piercing rivets. Some manufacturers, most notably Porsche, make extensive use of self-piercing rivets to join parts, as opposed to welding them, but the problem with these rivets is that they are extremely hard, and can often not be removed in any other way than drilling them out with specialized drill bits in an extremely slow and time-consuming process. As if this is not enough, body repairers also have to deal with-

While the BMW in this story contains carbon-fibre reinforcing rods in the roof rails, B-pillars, doors, rocker panels and various other places, these parts are relatively easy to replace. However, the same cannot be said for aluminium, magnesium, and CFRP (Carbon Fibre Reinforced) parts that are now seeing extensive use in a large variety of modern vehicles. These are in addition to SMC (Low and ultra-low-Density Sheet Molding Compounds) structural parts that cannot be repaired.

One particularly troublesome composite material is known as CNF (Cellulose Nano Fibre) which is made from wood fibres that are largely obtained from agricultural waste. The wood fibres are combined with plastics such as polypropylene, polycarbonate, and nylon in various proportions depending on the desired final strength of the part. The wood/plastics mix is then combined with various epoxy resins, and the semi-liquid material is then moulded, extruded, or pressed into the desired shape.

As a practical matter, parts made of CNF materials are up to five times stronger than similar parts made from conventional steel, but CNF-based parts weigh less than one-fifth of identical parts made of steel. One other noteworthy composite material is known as Amplitex, which consists of layers of resin-reinforced fabric. High-grade Amplitex not only matches the performance of high-grade carbon fibre, but it also has a smaller carbon footprint, meaning that is increasingly replacing carbon fibre in structural applications.

So while the increasing use of complex composite materials has resulted in lighter, stronger, and safer cars, the problem for body repairers is that these parts are extremely difficult to work with. More to the point though, these parts often require installation and fitment procedures that differ from those employed in the factory (to fit the same part) to ensure the proper and/or correct fitment of the replacement part.

Briefly, this was the problem with the BMW under discussion. Since a structural component (the bumper stiffener) was removed without providing overall support to the body shell, the stresses and tensions in the body shell that resulted from hundreds of parts made from disparate materials joined by different methods could very well have overloaded some joints, and particularly some joints that were glued together- albeit with space age adhesives.

At that point, it was not at all certain that one or more structural joints on the BMW had, in fact, suffered damage, but as the body repairer explained, there was no way of being sure one way or the other without investigating all potentially affected joints, panels, and parts using-

Apart from specialized jigs, fixtures, and high-tech measuring equipment such as the jig the BMW was clamped into, modern body repairers also need to invest in specialized welding equipment, and equally specialized foam injectors and applicators, since the rate at which some structural foams are injected determine whether (or not) they perform as intended.

Image source: https://cjme.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s10033-020-00526-3

Then there is the problem of removing self-piercing rivets, such as the example shown above. While the design of all self-piercing rivets follow the same general pattern, only some types of self-piercing rivets can be drilled out, as we mentioned earlier. In some cases, most notably on Porsche and BMW vehicles, these rivets can only be extracted with a special rivet gun that welds a stud onto the rivet, which stud the gun then uses to pull the rivet out of the joint. Note that these rivets cannot be drilled out: the only way to extract them without causing potentially irreparable damage to the parts under repair is to use the right tools to remove them.

Other specialized tools include dealer-grade scan tools to a) verify the operation of all ADAS and other safety systems and b) calibrate all ADAS systems after all body repairs. Moreover, the requirement to maintain dealer grade scan tools comes with the added cost of maintaining expensive subscriptions to third-party resources to access relevant repair and service information, which leaves us with this-

As it turned out, the BMW did not suffer lasting structural damage, and the body repairer was able to "straighten out" the car by reattaching a new bumper stiffener according to OEM-specified procedures. The process to disassemble, measure, and reassemble the car took more than a week and cost several thousand dollars, which was ironic, seeing that the car's owner wanted to save some money by doing the job himself. Nonetheless, the repair was successful since the plastic bumper was centred perfectly, and the blind-spot monitoring and other systems have not failed since the repair.

So what caused the multiple repeated failures of the blind-spot monitoring system on this particular BMW? According to the body repairer, the primary cause was a vibration in the rear part of the car. Even though no vibrations were evident, the fact that the bumper stiffener had been installed incorrectly caused high-frequency vibrations that disabled the radar transponders when the vibration frequency exceeded a maximum allowable threshold. Somehow, both this writer and the dealership technician had overlooked this possibility, but since no detectable vibration was present on the vehicle when we had it in our care, we can perhaps be forgiven for this oversight.

As far as we as mechanics are concerned, however, the most important takeaway from this tale is that modern car body shells differ from those of twenty years ago in the same way that wheelbarrows differ from modern Italian supercars. So this comparison may be a bit hyperbolic, but in the words of the body repairer, who is an expert in his field, it is no longer possible to fix accident damage by pulling a car straight. Doing so might break an adhesive bond or cause irreparable damage to safety critical parts and components that are invisible because they may be hidden deep within the structure of the body shell, which largely explains the presence of so many cars in salvage yards that show relatively little external damage.

As a final thought, this writer must admit that he knew nothing of how modern car bodies are designed and constructed before this BMW had crashed into a garden gnome. This fact has since made this writer wonder how many cases of un-diagnosable uneven tyre wear, rattles, squeaks, and other gremlins such as repeated ADAS system failures he had seen over the past two decades were directly related to poorly executed body repairs, or worse, by body repairs that should not have been performed in the first place.

Note that this writer is not suggesting that we should involve body repairers every time we run into a tricky or weird problem. Having said that though, modern car body shells are as complex as the mechanical and electronic systems we work on every day, so who knows if the rattle you spent hours trying to pin down yesterday was not caused by a broken or loose glued-in, 3D-printed composite part you did not know existed? Who knows, it might just be worth calling up your friendly local body repairer to check on that possibility…