At first reading, newcomers to the car repair industry might see a glaring contradiction in the title of this article, because how can being lazy make you a good mechanic? To some, the above title might contain contradictory terms, but this writer can assure all readers that in the context of this article, “lazy” does not necessarily translate into “bad”, nor does it necessarily mean that a “lazy” mechanic is an idle, unproductive, or inefficient mechanic. Quite the opposite is true, more often than not, and in this article, we will explain how you too, can be a lazy, but outstanding mechanic at the same time. First things first though, so let us start by saying that-

This writer has had countless opportunities during his three-decades-long career not only as a workshop owner and employer but also as a working mechanic, to study human nature in general and the human condition as it relates to mechanics, in particular. Many of the things that he has learned are irrelevant to this discussion, but one thing that stands out above all others is that for the most part, there are only two kinds of mechanics, or more precisely, that mechanics fall into one of two broad categories, these categories being-

Hard workers

The first category consists of hard workers, but there is a caveat to this; the caveat being that hard workers are not necessarily productive workers or workers who do not believe that automotive engineers are not idiots. Limited space precludes a full and comprehensive defence of this belief, but some so-called repairs made by some members of this category of mechanics that have passed through this writer’s workshop involved the bypassing critical safety systems, and/or a total disregard for the safety and/or interests of their customers. There are too many instances of this to list them all here, but we will discuss two such cases a bit later on.

Essentially, this category of mechanics can spend an entire day working themselves ragged without producing much in the way of effective, reliable, or long-term positive resolutions of their customers’ concerns. However, in the interests of fairness, it must be said that this writer has had some opportunities to witness occasional flashes of diagnostic brilliance in some members of this category of mechanics.

Lazy, but productive mechanics

Again, this might sound like a contradiction in terms, but truth is that very few, if any, mechanics like doing anything more than is absolutely required to address a customer's concern. Note that this is not the same as saying that most mechanics leave some things undone as a matter of principle; what this means is that most productive mechanics first determine the exact nature of the problem before they do anything to fix it.

For instance, productive and efficient will mechanics will never remove an engine from a vehicle to repair an oil leak if the leak can be repaired successfully without removing the engine. This is admittedly an extreme example, but it illustrates the point that you don’t have to work yourself ragged to fix something when there are easier and more effective ways to perform a complete repair. We further illustrate this point when we discuss the same two cases we mentioned earlier, which brings us to the idea that-

The concept of laziness being a process is not an easy one to explain, but let us attempt an explanation, anyway-

Most car-repair oriented websites/resources, including this one, host a multitude of articles and other resources that describe, among other things, a), the need to have a well-thought-out diagnostic process in place before you start a repair process, and b), the need to stick to your diagnostic process once you have devised one.

We need not rehash the content of any of these articles here, but suffice to say that all authors of such articles largely agree on the basics of how a well-thought-out diagnostic process should be arrived at, and we also do not need to rehash any of that here. However, the one thing that is missing from most of these kinds of articles/resources is the point that while there are often many ways to arrive at a definitive diagnosis, knowing what the problem is, does not necessarily translate into knowing how to perform a complete repair of the problem.

The term “complete repair” means different things to different people, but to the people whose opinions on this matter the most, i.e., our customers, a complete repair means one that resolves a concern definitively, reliably, and if possible, permanently. While employers and workshop managements largely agree with customers on this point, employers and workshop managements typically also require that complete repairs be performed without time, energy, and most importantly, money, being wasted at any point in the repair process.

If you are new to the car repair industry, regardless of whether you are in the dealership or independent sphere, this might sound like either a very tall order, or a proverbial walk in the park with your point of view depending on things like your level of training/skill, confidence, and attitude towards both life and your job. Most importantly though, your point of view depends on your problem-solving skills, and your ability to visualise how the various systems on a vehicle work and interact with each other.

We stated earlier that lazy is a process, but what does this statement mean in relation to the preceding paragraphs? It simply means this; mechanics that view the need to perform complete repairs effectively as a tall order experience laziness as a state of mind*, because they are somehow able to think of problems to suit all solutions.

* This statement is made purely based on this writer's observations made over many years, and is not intended to malign, insult, or belittle any person or group of persons. In the interests of fairness to all, it must also be stated that what is often perceived as “laziness” is often the result of a mechanic's personal circumstances that have taken a turn for the worse or a mechanic's (sometimes belated) realisation that he is in the wrong line of work.

On the other hand, mechanics that see the process of performing complete repairs effectively as a walk in the park are lazy in the sense that they can perform complete repairs while expending the minimum amount of effort doing so without wasting time, energy, and/or money in the process, which brings us to the-

We need not delve into the psychology of personal gratification here, beyond saying that all people who perform useful work have an innate need to be recognised for their efforts. As this relates to mechanics, at least in this writer’s experience, most successful mechanics find the sense of personal accomplishment and pride they derive from their work to be sufficiently rewarding to not need constant verbal validation from colleagues and/or employers.

However, attaining this state of mind (some would say, a state of enlightenment) requires that one follows a certain process, the five principal points of which we list below-

If you are an experienced technician, you have no doubt heard and/or read these five points countless times before, but have you ever considered the possibility that actually following or implementing them consistently and intelligently could make you a better mechanic, while significantly reducing the time you spend actually working, at the same time?

Of course, by “working” we mean doing things like-

There are many other possible examples we could list here, but the point is that most of us have fallen into similar traps at some point in our careers, but mechanics who have developed laziness to a fine art will tell you that it never happens to them, simply because they hate doing the extra work. Moreover, to some junior mechanics, it might look like some of their senior colleagues have access to some kind of magic because they manage to turn around high numbers of vehicles every day, they (almost) never have comebacks, and they never seem to break out in a sweat.

We stated elsewhere that we would discuss two practical examples of laziness in mechanics being a good thing, so let us start with the-

The owner of this 1988 vintage Sentra brought the vehicle to us after three other workshops had failed to find and fix an intermittent overheating issue. According to the customer, the vehicle would only overheat while waiting at stop signs and traffic lights, but not predictably, not always to the same degree, and only rarely during slow driving in heavy traffic. The customer also added that he had not noticed any meaningful coolant losses.

The previous workshops were not averse to issuing repair bills for their failed attempts to fix the problem, though, so we had a complete record of what previous attempts to fix the issue entailed, a summary of which is given below-

Our resident diagnostician is extraordinarily lazy, so he perused the provided documents for a bit before asking the customer if he would mind waiting for a definitive diagnosis. He explained to the customer that clogged radiators do not let engines overheat some of the time, and thermostats typically don’t fail intermittently- they work, or they don’t work, which was his way of saying that the previous workshops were talking rubbish.

Long story short- the diagnostician noted to this writer that none of the previous workshops had checked the OBD 1-era ECU for fault codes, so he ran through all five diagnostic modes by counting the flashing MIL lights, and concluded that the ECU was good. Next, he used his 5-gas analyser to check for hydrocarbons in the coolant reservoir and found none, which proved him right about the supposed blown and/or damaged cylinder head or gasket. Next, he took temperature readings on all radiator hoses and at multiple points on the radiator core, which proved that there were no coolant circulation issues.

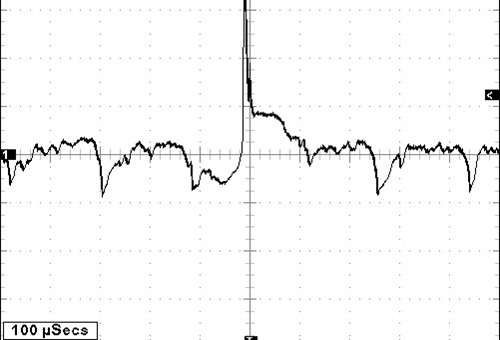

All of this took less than 20 minutes, so the only remaining thing to check was the fan motor itself, even though it started and ran fine every time he applied direct power to it with jumper wires. Thus, he connected his digital storage oscilloscope to the motor, and allowed the engine to run at a fast idle until the motor started, which produced this waveform-

Image source: https://www.searchautoparts.com/sites/www.searchautoparts.com/files/images/ma0814_drive1.bmp

This is just a snippet from a five-second capture, but the current peak we see here is clear proof of the real cause of the problem. This peak is evidence of a shorted armature segment, so every time the fan motor stopped on this segment, it could naturally not start again. However, as soon as the vehicle started moving, vibration and airflow through the radiator would swing the fan just a bit, thus bringing the brushes into contact with good segments on the armature, which then allowed the fan to start and run again. The next time the motor stopped on the shorted segment, it would not start again, and so on, which explained the intermittent nature of the overheating problem- it just depended on how the fan motor stopped.

So why did one mechanic think of testing the fan motor, while so many others did not? Maybe, it was because the other mechanics laboured under an over-reliance on OBD II fault detection technology, not knowing that they were dealing with an OBD I vehicle, which incidentally, explains the note on one invoice that said they were unable to connect a scan tool to the vehicle.

Then again, perhaps they could not reduce the problem to its simplest form, or perhaps they could not replicate the problem. Who knows what they thought or did not think, but in this writer's opinion, the problem could have been found and resolved by the first workshop had they used some common sense, some problem-solving ability coupled with some basic knowledge, and a healthy aversion to unnecessary work, which brings us to the case of the-

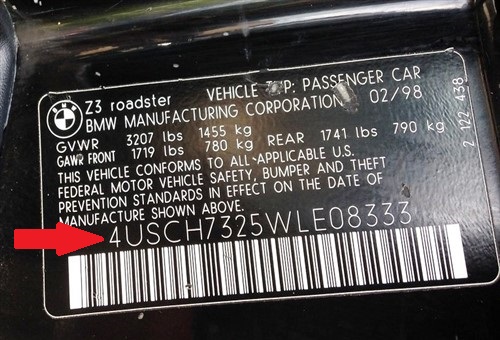

Image source: Public Domain

VIN numbers have been described as “windows into the souls of cars”, and this proved to be particularly true in the case of a BMW roadster that arrived at this writer's workshop on the back of a recovery truck a few years ago. The owner was distraught since a previous workshop had ripped out most of the dashboard, major wiring harnesses were opened, the carpets had been ripped up, and the instrument cluster was disconnected, which is perhaps a topic for another discussion.

Nonetheless, the vehicles' female owner burst into tears as she explained the problem. She said that the vehicle's battery had died one day, but having the battery replaced at a local workshop "must have broken something" because while the engine cranked over normally with the new battery, it would not start with the new battery. The workshop that replaced the battery offered to "have a look”, but three weeks later her car was in pieces, she had to pay the workshop for some “sort of computer”, and her car was still in pieces. She needed help, she said, and if it would help us in any way, the old “computer” was available for our inspection.

Our lazy diagnostician listened to this tale of woe in silence but rummaged in the wrecked BMW until he found the old ECU. Next, he pulled the used replacement ECU from the car, wrote down the BMW's VIN, and entered both the VIN and the (replacement) ECU's id into an official BMW database. The results confirmed what he expected; while the replacement ECU was programmed for a BMW roadster, it was intended for use on a different model. In this case, the ECU was intended for use on a model that was four years newer than the customer’s vehicle, hence the no-start condition.

All of this took less than ten minutes, and while one can ask why the mechanics at the previous workshop did not make sure that the replacement ECU’s id matched the vehicles’ VIN, the question remains unanswered, as do so many other things in life.

Long story short; a suitable rebuilt replacement ECU was installed, all wiring was checked for signs of damage, all wiring connectors were double-checked, a new battery was installed, and the BMW started up without trouble. So, did the diagnostician know anything about BMW roadsters that the previous workshop did not?

Maybe, but this writer is more inclined to the idea that the diagnosticians’ inherent laziness motivated him to listen to his intuition, which told him that given the way the car was ripped apart, it was most unlikely that anybody at the previous workshop would have bothered to check the replacement ECU's id against the vehicle’s VIN.

To restore this unhappy customers’ faith in humanity in general, and in mechanics in particular, we offered to reassemble her car for a hugely discounted fee. She accepted the offer and she still has the car, which leaves us with this-

The two example cases we discussed above could have turned out very differently; for one thing, we could have repeated everything that had been done before and fallen into the same rabbit holes, with the same unfortunate results. Lucky for both our customers and us though, we had a diagnostician who believed, and firmly so, that hard work is for the birds and should, therefore, be avoided whenever possible. This opinion has served him, our customers, and us well over the years, and it will no doubt serve you well, too.

We hope that this writer's observations have served to inspire at least some readers to become lazy mechanics or failing that, to at least recognise that there is not always a need to work one’s self ragged for no good reason. All it takes is a little practice.