If you have been in the car repair industry for a long time, you will probably agree that BMW petrol direct injection engines seem to be more prone to issues like-

- and general drivability issues than the direct petrol injection engines made by almost all other manufacturers.

You will likely also agree that despite our best efforts to resolve the issues listed above, they often don’t stay resolved for very long before recurring. So, have you ever wondered why we can’t seem to resolve some issues on BMW direct injection engines definitively and reliably over the medium to long term? This is perhaps a loaded question because some BMW engine issues are caused by many variable factors, but this article will attempt to answer this question in simple terms, some of which may surprise you. Before we get to specifics, though, let us look at-

This writer has often said in these pages that diagnostic flow charts are less than useless because they never address the root cause(s) of a problem, and this remains true of not only BMW diagnostic flow charts but those of other manufacturers as well. The reason for this is that flow charts are designed to help technicians resolve one or more symptoms of a problem in the shortest possible time, as opposed to addressing the root causes of the problem. Kind of like sticking a Band-Aid over a gunshot wound to the head, if you will.

However, despite BMW being a premium car brand, this writer has never seen (or heard of) official BMW resources that address all the possible causes of failures or malfunctions in closed crankcase ventilation systems. The same is true of steadily increasing oil consumption and intermittent misfires that affect all the cylinders.

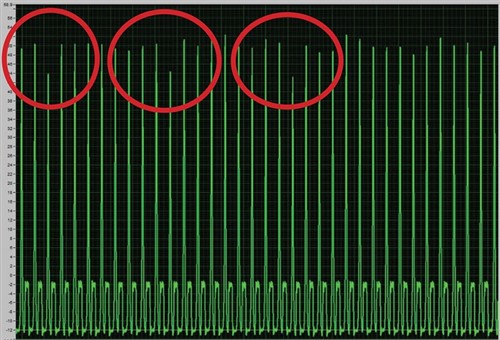

We can list many other examples here, but in the case of intermittent misfires that affect all the cylinders, BMW recommends that we do a static cylinder leak-down test and although this test does have a few useful applications, a static leak-down test also has severe limitations in terms of the kinds of issues it can identify definitively. Consider the image below-

Image source: https://automotivetechinfo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/in-cylinder-running-compression-waveform-misfire.jpg

This waveform was taken from a BMW direct injection engine that exhibited random misfires across all cylinders. The engine was running at idling speed and so the tall green spikes represent peak combustion pressures, which, incidentally, differ markedly between cylinders. However, the most noticeable thing about this waveform is that it shows serious compression losses occurring in random cylinders, as shown by the red circles.

So, what do you suppose caused random cylinders to lose significant amounts of combustion pressure only to recover on subsequent engine cycles? Upon investigation it turned out that the intake valves had heavy carbon deposits on them, which disrupted the flow dynamics of the intake air passing over them differently as the valves rotated in the cylinder head. Remember, this was a direct injection engine, which requires the intake air to tumble into the cylinders in a specific way to ensure complete combustion; ergo, bad airflow dynamics equalled poor combustion, and hence the random misfires.

More to the point, do you think a static cylinder leak-down test would have detected this problem? As a practical matter, such a test would not have detected the cause of the misfire because the engine would not have rotated fast enough to induce valve rotation. Moreover, if the valves were not leaking (they were not) a leak-down test, or even a relative compression test at cranking speed, would almost certainly not have shown the random compression losses and, yet, BMW recommends a static leak-down test to diagnose random misfires across all the cylinders, which brings us to-

Another example of BMW is not telling us everything we need to know will suffice. This example involves catalytic converter efficiency codes and even recurring catalytic converter failures, but have you ever seen official BMW repair /service information that mentions “toxic”, degraded, unsuitable, or fuel-contaminated engine oil as a cause of catalytic converter failures?

Again, more to the point; have you ever seen official BMW service information that specifically mentions poor cylinder sealing and even marginally excessive ring blow-by as possible causes of catalytic converter issues or failures? This writer has certainly never seen poor cylinder sealing listed as a (possible) cause of catalytic converter failures mentioned in BMW service information.

However, long experience with issues like (among many others) coked-up turbochargers, VANOS and timing chain faults especially on N20 engines, steadily increasing oil consumption, noticeable engine power losses and Valvetronic faults, will eventually lead you to rethink your diagnostic approach to these issues. The fact is that one's approach to a specific issue can greatly affect the diagnostic outcome and with it, the reliability and efficacy of repairs based on our chosen diagnostic strategies.

So, what does this mean on a practical level? It simply means that we often look for the cause of issues with fuel injectors, PCV systems, VANOS camshaft actuators, timing chains, turbochargers, and many others in the wrong places because the real cause(s) of our problems are not visible- neither to us nor to our scan tools, so let us look at-

The problem(s) with carbon formation and depositing in BMW direct injection engines is that, it is a) sometimes a slow process, and b) we often don't know how serious carbon build-ups have become until parts or system failures occur or the vehicle develops serious drivability problems.

In practice, the rate of carbon deposition is largely dependent on how a vehicle is used but as a rule of thumb, the rate of deposition accelerates when a vehicle is used predominantly for short trips, so briefly, here is how the vicious cycle mentioned earlier works-

Once carbon starts to build up on valves and piston crowns, the engine has already suffered some degree of mechanical damage that influences combustion, and when combustion is affected more carbon accumulates because of the reduced efficiency of the combustion process. Therefore, poor combustion creates more engine damage, which increases the rate of carbon deposition and so on until a part failure occurs.

However, the rate of carbon deposition is not necessarily (or always) linearly related to the progression of mechanical engine damage. This is because things like different oil brands that contain different additive packages, varying fuel quality, different driving styles, and vehicle use all have varying effects on carbon formation and deposition rates in BMW direct injection engines, which raises the question of-

Image source: https://a6s.info/en/exploitation/209-water-in-gas-tank

Although all E10 petrol blends have to conform to the current fuel quality standards, quality standards cannot prevent ethanol from separating from petrol, such as can be seen in the sample of E10 fuel shown here that had been allowed to stand undisturbed for about 14 days, but what exactly are we looking at here? Let’s see what the arrows mean-

It is important because apart from clogging injectors, the paraffinic wax molecules undergo meaningful structural changes when they are subjected to the heat and pressure of the combustion process. We need not delve into the intricacies of combustion chemistry here beyond saying that during combustion, the wax molecules transform into the hard carbon deposits we see on the valves shown here. It is also worth mentioning that this type of carbon is chemically much different from the soft powdery carbon deposits we often see in combustion chambers and on piston crowns, so here’s the problem-

How would you diagnose, say, random misfires across all the cylinders? Would you first spend a significant amount of time testing and checking the ignition system, or would you suspect a significant amount of carbon deposition on the valves and in the intake manifold? Then again, how would you justify the cost of removing the intake manifold to check the valves to your customer if you are not sure there are, in fact, heavy carbon deposits on the valves? This is a difficult position to be in, but for the moment, we are left with-

In Part 2 of this two-part article, we will attempt to answer these questions and also provide a possible but controversial solution to the problem of carbon deposition in direct injection BMW engines.